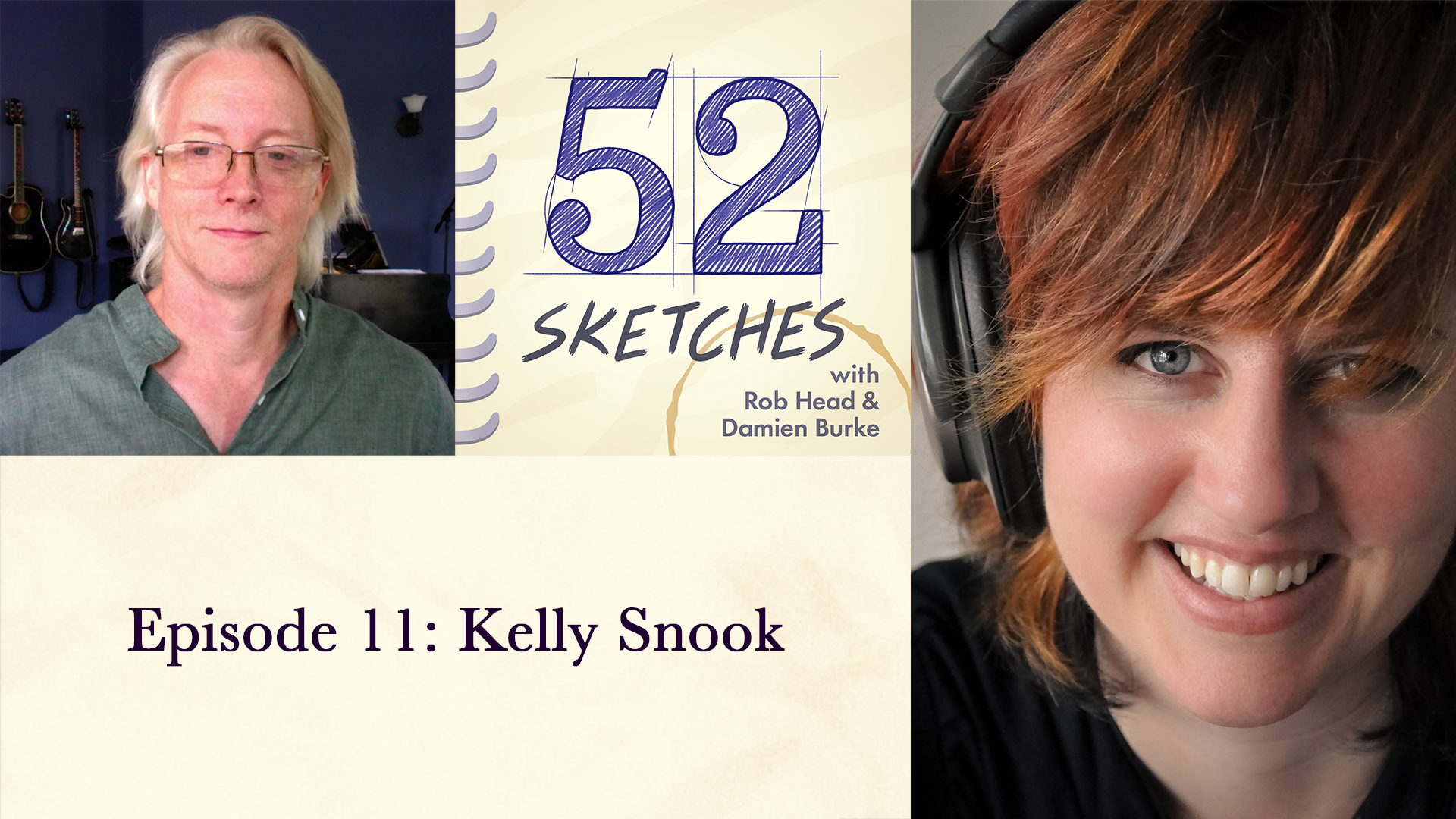

Episode 11: Music Producer and Technologist Kelly Snook

Subscribe: RSS | Apple | Spotify | Google | Sticher | Overcast | iHeart | YouTube

Music producer and technologist Kelly Snook discusses growing up as a musician, becoming a rocket scientist, how Imogen Heap lured her away from NASA, how Kepler used music to launch modern astronomy, and using music today as a tool to understand ourselves and the universe.

- Kelly Snook’s website

- Kelly Snook on the Music Gloves She Made for Imogen Heap

- Kepler Concordia

- Concordia on Patreon

- Kelly Snook on Bandcamp

- Imperial Mathematicians

- Kelly Snook’s closing keynote at the Audio Developer Conference

- Imogen Heap

Transcript

Rob Head 0:01 The 52 Sketches podcast. Today, Episode 11, music producer and music technologist Kelly Snook.

Jennifer Head 0:12 Welcome to 52 Sketches, a podcast about creativity and creative practices. Here’s your host, Rob Head.

Rob Head 0:23 Welcome to the 52 Sketches podcast. This is your host, Rob Head. We are here today to chat about living a creative life, the art and science of bringing truth and beauty into the world. So today, I welcome rocket scientist turned music producer Kelly Snook, Dr. Kelly Snook, earned a PhD in aerospace engineering from Stanford University and worked at NASA for many years as a research scientist. She left NASA to pursue music production and music technology, working with such stellar artists as Imogen Heap and Ariana Grande. She now teaches at the University of Brighton, and is the inventor of experimental digital instruments such as the MiMu gloves that turn gesture into music. So Kelly, I am delighted to welcome you to the podcast.

Kelly Snook 1:10 Thank you. It’s lovely to be here.

Rob Head 1:13 Wonderful. So your background is, shall we say, you know, compared to most of our guests 52. So let’s, let’s tell you about 11 years, it’s pretty clear from your technologist, Kelly, that you are a science kid. Yeah.

Kelly Snook 1:31 Actually, I was always a music kid. I know. Yeah. But I when it came time to choose what to do with my life, which they make you really feel like you have to know when you’re 16 I was terrified to do music. I was so terrified that that engineering seemed like the easy way out. So I chose engineering over music. And I always felt that I was I was, in a way dodging my duty to my purpose. So I always, I always did keep it tried to keep a little hand in music, even when I was in school wasn’t sometimes more successfully than others. But um, yeah, really. It was always music that was calling to me.

Rob Head 2:22 So did you play certain instruments as a kid growing up playing band at schools?

Kelly Snook 2:27 I did. I did all of that. I played the piano, mainly. But then I also played, I went through a series of different instruments before in fifth grade settling on the oboe. I think I had a stone, the bassoon. I was too heavy cello with the violin, the baritone. But I chose. I chose the oboe eventually. And the piano was always there. But that was back in the days when I thought those were my choices. I didn’t know about music production in those days,

Rob Head 3:00 right? Yeah, absolutely. Hmm. It’s fascinating. I grew up in sort of a similar fashion. And I went to the University of Maryland thinking I was going to study aerospace engineering, like you did, but did the irresponsible thing and drifted around and got a degree in dance. But lucky for me, the the web came along, and I was able to make a living in technology even though I did you know, nobody had a degree in web technology. So it was sort of free for all. But anyway, so that was, that was a good time. Okay, so so you, you play all these instruments, and you end up going to university for engineering. Did music continue to call you to you during that time? Or tell us about your your schooling and your early career?

Kelly Snook 3:51 It really did. I, when I was a freshman at the University of Colorado, I, I played oboe in the orchestra. I, I kind of had decided that I was going to do music, air quotes on the side and air quotes. It wasn’t until I was into my almost finished with my PhD at Stanford that I I got this overwhelming sense that it wasn’t enough for me to do it on the side, but then still thinking I needed to do it on the side. I did for a very brief moment about a few months before I handed in my PhD. I went and started to look into what it would cost it would take to get a music degree instead of instead of an aerospace engineering degree. And that just was too at that point. It was really too late. So instead, what I did was I well, while I was a graduate student, I’d also pursued some Really interesting musical forms. For a few years I was in the Stanford Taiko ensemble, which is a Japanese drumming. Kind of.

Rob Head 5:08 Yeah. We have a taiko guy here in Ashland, Oregon who’s Yeah, masterful. Yeah,

Kelly Snook 5:14 yeah. And it’s actually not possible to say whether that’s dance or martial art or music. It’s kind of all the things together. I learned a lot about myself and about it, I think about music.

Rob Head 5:25 It’s the only instrument I’ve seen where you have to literally train, workout, to supplant,

Kelly Snook 5:32 yeah, and so I did a lot of my years as a graduate student were really focused on taiko and not on aerospace engineering, because the ensemble, the ensemble also was very serious. And we would do, it was more than 40 hours a week of a physical training, and we made our own drums and we made our own our own outfits, performance outfits. And, you know, it was a very, it was a serious practice. It wasn’t just, it wasn’t just a hobby. So right, um, you know, that I always, more and more as I was going, going along, in my engineering degree, I was trying to dig, I was getting a sense that I wasn’t just gonna build rockets, I was going to maybe try and figure out how to do more. And But it wasn’t until I had already been working as a civil servant at NASA for a year that I, I figured out how to buy by a proper recording studio, and start learning how to produce music. So it was a you know, I had already finished my PhD. In the end, I decided to just get it because I was so close. And then and then figure out how to learn music production, I knew that if I were going to make music, the way that I needed to make music, I would need to learn the technology. And the thing that made me realize that was one night, I came home really late at night and heard a song of Imogen Heap on the radio and, and just jolted me into realizing that I needed to be putting energy into figuring out how to make how to make music. It was it wasn’t a good feeling. It was a kind of a panic feeling that was caused me to look into or what would what would it take for me to get a music degree, but that the degree was not the answer. Really. It was just putting in the time and the tech

Rob Head 7:31 right? The skills. Yeah, I’ve had a couple of moments of like, where you’re just completely arrested by a particular artist. I remember, I had to pull the car over when I heard Tori Amos for the first time.

Kelly Snook 7:43 Yeah, Sam, similar with Tori. And around the same time, she was also making music. Yeah, she was just putting music. I was late 90s, you know, and yes, the music was starting to come out that was like, Oh, this is this sounds like what’s in me, somebody else is making my music my way out, like, oh, gosh, what am I doing? Why am I Why am I not doing this? Right?

Rob Head 8:07 So So it sounds like there’s sort of a sense of something calling to you, even though you’re you’re doing you’re living a life that that most people would find, you know, at the sort of peak of our society, you’ve done the right thing. You’ve gotten all the degrees you’re working at NASA, you could like couldn’t be, you know, more responsible and more contributing to society in the way that we normally frame that. And yet, it sounds like, yeah, so would you describe it as a calling? Or I mean, like how?

Kelly Snook 8:39 Yeah, very much so. But it was one that I was trying very hard to ignore, in terms of a profession. Because, you know, and part of it was a response to the clearly inappropriate way that society handles art and music. And, you know, I wanted very, very much to be creative, and for my life to be about music, but I didn’t want it to be about me. And it was it’s really impossible to separate those those things in the traditional music industry. music industry is about glorifying individuals. And yes, yeah, and people and their image and their bodies, and it’s so materialistic that I couldn’t see a pathway for for leading a life that was supported by profession and music without succumbing to what I saw as just a completely inappropriate music industry. And I couldn’t reconcile those things. So it was very much of this calling that I needed to ignore, or, or do on the side or like it was very confusing for me. Until a pretty specific moment a few years later. that I had, I started to have an inkling of what it really looked like what the calling really was, it definitely isn’t being a rock star, or being a concert pianist, or those things that I that’s really all I knew when I was a child, you know, I, if I were going to go into music, it’s either like, being a performer or being a recording artist or being a, you know, I don’t know, being some front and center stage in a performance situation, right, or playing in an orchestra, an ensemble or? Yeah, those were those to me, that was what it meant, if I were going to do music. Mm hmm.

Rob Head 10:39 You mentioned Imogen Heap. And the first time I heard of you actually was from, I think, a mutual friend that lives in Palo Alto. And they mentioned that maybe it was Imogen Heap that lured you away finally from NASA.

Kelly Snook 10:52 It was. Yeah.

Rob Head 10:53 Tell us that story.

Yeah. How did you make that transition?

Kelly Snook 10:57 Yeah, so um, you know, as I had explained, image in images, music had a really big impact on me, in that critical time when I was doing my PhD. It was her first it was her first album, really, I don’t really actually listen to music very much. But I’ve listened to that pretty, pretty obsessively. And then kind of got busy doing other things for many years, and I started producing music on my own. And while I was working at NASA, and so we kicked just cut a few to eight years later. And by this time, I’m in Washington, DC, my studios there I’ve been, I’ve been producing music for a few years, with independent artists. And

Rob Head 11:39 already working in Goddard Space Flight Center. I

Kelly Snook 11:42 was I was working at headquarters and at Goddard both when I was living in DC and I see and I was just watching movie at the end of it was let go the song Let go. That image ended with Guy Sigsworth went in in their duo called Frou Frou. And I was just jolted back into oh my gosh, Imogen Heap is still making music. Of course she is. And wow, this is incredible. And then I realized because I had been producing music for so long that what I loved about one of the things I loved about images, music was her production and also guys production guy, six months production. And now that I’ve been producing, I was listening to music in a completely new way. And I got in touch with guy Sigsworth at that moment, just to tell him how much I love his production and to I don’t know, just yeah, just to let him know. And he wrote right back, because he was he was really a NASA nerd, as well. And so he and I started this pen pal relationship for the next few years, that was fun to work with, you know, I would talk about space stuff, and he would talk about music stuff. And he, uh, you know, I learned a lot about string production from him. And, you know, I would I would just send an email, like, how did you get this? How did you do this string build and this, I started to listen to all the other artists that he produced and just producers here and, and so it was really through Guy’s influence on images, music production and images, also images production, that drew me back to pay attention to what she was doing, because I hadn’t really, I wasn’t, you know, listening to music. I wasn’t other than the music that I was producing. I was just, it was enough for me to just work at NASA and I make my own music. So I hadn’t been really listening a lot. And then, so then at one point, I was asked to give a talk in Japan that the Association for Baha’i Studies in Japan asked me to invited me to Japan to give a series of public lectures about the history of space science, and astronomy, on our collective understanding of ourselves. And so at this point, I was living in DC I was, I was around, maybe it was just before I moved to DC, but I was working at NASA, I was making music, but I wasn’t really thinking in the biggest possible picture about, about what what was, you know, what was the relationship between what I was doing and the history of human thought? You know, that’s the biggest possible question, and I was so daunted by this invitation. And I felt so you know, imposter syndrome-y about it, that I, I started reading and reading and studying for this for this tour, because I didn’t even I hadn’t even really even thought about the history of space science and astronomy and the impact on collective human thought. So yeah,

Rob Head 14:33 I think you immediately remind me of Carolyn Porco and her work with the “pale blue dot,” that image and what it says about humanity, and

Kelly Snook 14:42 yeah, I mean, I was, I had been thinking a little bit at NASA, because we were well, you know, I was working on strategic planning for the agency. And, you know, so in some sense I had, I was familiar with NASA strategic plan, which always has these really lofty things like an improved life on Earth, and Every goal or whatever, ends with something lofty like that and improve quality of life for mankind or something like that, but, but really like, oh, throughout all of history, I didn’t really know much about history. And so I was reading, you know, in studying for this, preparing for this trip I was, I was reading kind of normal history of science stuff. But then I also started reading the Baha’i writings about, especially ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s writings about, about the history of science. And there is a little bit in his writings about this. And ‘Abdu’l-Baha, in one tablet, he mentions—’Abdu’l-Baha is the son of the founder of the Baha’i Faith, and he was at he was talking at one point about, about the worldview, the understanding of the Sun being at the center of our solar system, and how that wasn’t always the case, and how the very early Greeks actually knew this. And for example, Pythagoras, and and those people doing that, and then it’s kind of debated, but ‘Abdu’l-Baha has said that this was known. And then Ptolemy, Ptolemy proposed a different, a different idea, which was that the Earth was at the center of everything. And Ptolemy, like, put out an actual written thing that started spreading and that worldview that the Earth was at the center, everything then became the worldview that was infused into everything

Rob Head 16:29 He had the publishing advantage.

Kelly Snook 16:31 Yeah. So keep it because he published it and also had good arguments for why it was that way. That’s what took hold for the next 1500 years. And it wasn’t until Copernicus came along, and proposed, again, at the center that the sun heliocentric right and so ‘Abdu’l-Baha actually had a tablet where he spoke about this, and I started thinking about that, like, oh, wow, yeah, that’s a huge misunderstanding and a mistake and knowledge that was propagated for 1500 years, and that cost many people their lives in trying to write that wrong. And, and it was only Kepler, really. And that was when I re-encountered the work of Kepler, because Kepler looked at at was the first person to figure it out mathematically, to prove Copernicus’s theory mathematically, to really figure out the mathematics behind how the solar system works. And what I didn’t know, I knew that part because I was an engineering student. And of course, we learned Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion. But at that point, what I did what I was face to face with in preparing for this talk, was that Kepler figured all of that out through music, and through a spiritual conviction that God’s organizing principle was harmony. And so using harmony, the spiritual principle of harmony, and the and the best data that existed in the moment, and insisting that the observations match the the mathematics, it was only through all we’re doing all of those things together. And using musical principles that he made this, that he essentially launched modern astronomy. So that was the moment where I was like, why are we not using music like this right now? Why? Why are we just playing with it? Like it’s a toy? Why aren’t we using it to understand our universe, and that was the beginning of my real, like, the light going on. Like, this is what this is, for the purposes for me, this is where it’s like figuring out how to use music as a tool to understand ourselves and to understand the universe. And, and so that was the beginning of this project that I’m still working on. That was that was 19 years ago. That was 2001. And I’m still starting on this project to build to build a musical system that allows us to learn about our, our realities, but yeah, that was that how did you

Rob Head 19:02 go from that realization to to getting pulled away? away from

Kelly Snook 19:07 right, so so right, okay, so, so that, so that was 2001. So by 2008, I was really itching to try and figure out how to do this. How do I, how do I, how do I figure out how do I build essentially, build a model of the solar system that’s playable as a musical instrument where I can learn about the physics. I didn’t know how to articulate it that way. I had no idea really what it was that I wanted to do, but I knew I had to do with using music as a scientific tool. And I knew that in order to do that, I was going to need to learn some new technological tools because at that point, all I could program in Fortran 77. That was all I knew. Wow. And that was not going to be enough to do to do what I wanted to do.

Rob Head 19:53 Yeah. For our listeners who who aren’t software developers, Fortran is a is a rather antiquated programming. language that doesn’t get a lot of new development these days,

Kelly Snook 20:02 NASA still uses it now. But you know, there was a lot going this was now 2008. And, you know, that was an explosion and in in programming tools and computer digital tools, and, you know, internet of things being born and that sort of thing. And I knew that I needed to figure I needed to learn some new tools. And so I, I applied to NASA, to send me to the Media Lab, there was a program called innovation ambassadors, where they were sending people from NASA out into the world, where there was innovation going on to figure out how to be innovative and bring that innovation back to NASA. So I used that as an opportunity to apply to be an innovation ambassador, and I went to the MIT Media Lab for a year. So this was, of course, really one of the biggest turning points of my, my life and my career, because I had an opportunity to just be it in this incredibly, incredibly innovative place for a whole year with no other requirements of me that I then that I understand, try and understand what makes it innovative. And, and that was when I had time really to, to watch imagens video blogs. And she in her video blog, she was talking about how she had a studio and she but she wanted to go on tour. And she wanted to needed someone to help her look after her studio. And I you know, I saw in the background, all the equipment in our studio, and it was all the same equipment that I use and new, including, like, in fact, the same brand of microphone, the same software the same, you know, and that I just spent the last eight years teaching myself. And so I wrote to Guy at one point, and

Rob Head 21:49 I knew I’d already had an established

Kelly Snook 21:50 and and by then I was like for three or four years guy guy and I had been exchanging emails. So I just wrote to him and said, Hey, do you have images, email address, and I I wasn’t planning on actually contacting or I didn’t feel ready. I hadn’t done anything musically that at all represented my own. I don’t know my own creativity or my own voice at all. I wasn’t. But But you know, I was also feeling embarrassed that I that I was so shy. So I said, Okay, well, let’s just get her email address. And then at some point, when I’m ready, I’ll contact her. Well, I wrote the guy. And then the next morning when I woke up, if you didn’t just send me your address, he he like, introduced me to her over email, and she wrote back had written back before I woke up. So I was kind of forced into, into corresponding with her. And so I just kind of suggested, well, maybe I could help you. And you know who I was, I wasn’t in the music industry. I wasn’t any anybody but right. But she was like, Oh, yeah, maybe that would be good. And she came and visited me at the Media Lab. And, you know, I introduced her to some of my friends that were doing really cool things, she was looking for new ways to interact with her music, on stage, new technologies. And one of my friends at the Media Lab or two of my friends had created this glove, that you could, you know, you could grab a note while you’re singing and manipulate the note. And she just, she saw that. And she was so excited about the possibilities for own music with a glove. She was like, Ah, that’s what I need. She immediately went back to the UK started working on it, I funding while I was still at the Media Lab, and then went back to NASA for a few months, but was really at that time that I understood that these technologies that we’re being developed and these tools that we have in, in music, art, actually, they’re the same tools. It’s It’s It’s like, it’s kind of agnostic, whether you want to use technology for science, or use it for communications, or use it for music, or use it for visual art, like the technology is technology. And really, it’s just technology to enable human creativity, whether that’s in the sciences, or in arts, or an exploration or whatever it is. And you know, it’s not really very much of a leap to go from working on technology for science to technology for music, so really not a leap at all. It just in our world, the world makes it seems like seem like it’s elite, but it’s not at all holy.

Rob Head 24:18 Yeah.

But you know, yeah. You mentioned in an interview that I saw on YouTube, that the pace with which things develop in the two worlds are dramatically different. So obviously doing government work at NASA, where, you know, my understanding is, you feel lucky if you do two missions, you know, in your career. Right, versus, you know, versus the, the art world where, you know, an artist might say, okay, we’re gonna build a glove and I’m going to be on stage with it in six months. You know, go

Kelly Snook 24:52 No, it was one month, it was not six months. It was you know, it was a ridiculous amount of development in a short time with very high stakes and Not no testing. That that was Yeah, it was it’s a completely different pace. Honestly, I’m much better suited to that faster pace, but it certainly is nerve racking and, and very, very stress inducing. So did

Rob Head 25:15 she pull you into the glove project? Is that how you ended up in her studio?

Kelly Snook 25:19 Well, she got the idea for the glove project while she was visiting me. So I kind of pulled her in either way, it that was where it was kind of the idea of it was born, she and Tom Mitchell started working on it, even before I got there, but I went soon after, not just to work on the gloves, but she was working, she was starting a new project, she was starting her sparks album, which is essentially 13 completely different projects. All is like a project album. So each song is a project and was only one song on that album, that was the glove, the glove song was called me the machine. But for that song, she wanted to completely write, record and perform a song with gloves, which is like a whole different technology requirements for those things, you know, performing is one thing, but creating is a whole different is almost like a different set of requirements for that technology. Right. And so we started we did start immediately, you know, she and Tom had already started looking at gloves. And one of the first packages to arrive at the house where I was living next door to her when I got there in 2010 was the five d t glove that we started with, which was an off the shelf glove that you could buy. So we started kind of low key at the beginning, it was only one of the many projects and since I was her musical assistant, I was her studio manager and musical assistant, I was really really consumed 24 seven was supporting all the different project, I mean, one practice to give you an idea of one project involved traveling to China for two months and setting up a recording studio and and completely writing and recording a song from different places in show in there in China. So that’s just an enormous undertaking to ship an entire studios worth of gear, so that immigrant can write his record and write a song in China. You know, so these were not small projects, we weren’t just wasn’t imaging just sitting in our studio, creating in with, you know, with the tools that she had, she was crowds. She was one of the first people to crowdsource the first song was completely crowd sourced from, from people from around the world sounds from around the world. And she made the first song from that, you know, and all of those were pretty ahead of their time in terms of using technology to, to to get participation from from people. And

Rob Head 27:57 so so at that point, you’re working full time for Imogen Heap.

Kelly Snook 28:00 Yeah, yeah.

Rob Head 28:01 And what year did that transition happen?

Kelly Snook 28:04 Well, I kind of, we decided to test things out, there was a lot of other stuff going on. My husband is bred at my ex husband, who was my husband at the time was British and his mother lived in England, there was some medical stuff going on. So I took some medical leave from NASA at the beginning and went to the UK to just test out whether image, whether that would be a fit, even whether it would be possible to make that that leap. So there was 2010 was an experimental year. And the main project that I worked on with her during that during 2010 was a big performance at Royal Albert Hall with a crowd sourced video project with an orchestra and a choir, which culminated in October. And then I went back and just had to decide, I went back to NASA for a few months to just make the decision. Like, is this something that I’m gonna really do?

Rob Head 28:59 And how did you feel about that? Did you? Did you still feel like, Well, that was crazy. And, or did you feel like, Oh, that’s definitely what I need to be doing?

Kelly Snook 29:08 No, I you know, I thought that, I mean, it was pretty obvious that it was definitely closer to my, to my purpose, but I it was also way harder to leave NASA than I thought it than I ever thought it was gonna be. It was really, really hard for me because a lot of my identity was wrapped up in at more than I was wrapped up in being a NASA scientist. And yeah, you know, and it was a very secure job, you if you’re a civil servant, you know, that’s not something that you leave, you know, it’s a job for life. Really?

Rob Head 29:46 Yeah. I worked at Goddard for a summer book between high school and college as an internship. And one of the things that I noticed is that it’s almost just a standing desk. joke with everyone. Everyone is planning to leave NASA but never does.

Kelly Snook 30:04 Yeah, yes. It’s you know, I didn’t expect it to be so hard. And it wasn’t because I don’t know why. I don’t know why it was so

Rob Head 30:13 well, it’s a stable job. And it’s a good salary.

Kelly Snook 30:15 Yeah, I mean, you know, like my friends and that, yeah, my first class and we’re like, so do you have a contract? And? And I was like, No, anything in writing? No, you have a insurance? No. Everything save everything. Yeah. table and going into completely into the unknown. And I was 41. You know, it wasn’t like I was that young. Right. Right. And it was it was.

Yeah, was not a

Rob Head 30:48 not a safe bet.

Kelly Snook 30:49 No, it was there was nothing safe about it. And I’m not ever I wasn’t ever wanted that I really needed a lot of safety. But this was this was unsafe, even for me. And honestly, it was as hard as I mean, the fear was very important. And, and real. And it turned out to be worth like, it was actually everything that I was afraid of was is something that happened, and it was really, really hard. So it wasn’t like it was unfounded fear, or it was just, it’s like, there’s a reason why people don’t do this. It’s

Rob Head 31:27 really hard.

Kelly Snook 31:30 It’s Yeah, hard.

I’m feeling the impact of it now.

Rob Head 31:33 Yeah, yeah. So

Kelly Snook 31:35 yeah, definitely. That’s how that’s how I got to it. Yeah.

Rob Head 31:40 So talk to me about how I understand that there’s a glove project called MIMO. Is that right?

Kelly Snook 31:46 Me Mew Mew.

Rob Head 31:47 mew. Okay, can you tell us about that? Is that is that? Has that reached? productization? Is that Yeah, an ongoing?

Kelly Snook 31:54 Right. Yeah. So so what we started then in 2010, then it became it started to become very clear, even in those first years. 2012 was when we did the, the big she did the big performance in her in her garden. And a big dome that she built with it was streamed to one and a half million people with the glove. That was the that was like the very, that was when things were starting to develop. But we realized very early on just by the number of invitations, she was getting to speak at wired and Ted, and you know, that this was something that lots of people were going to want. And so at some point, we had to start transitioning our thinking from Okay, what does image in one need to? What would make this a powerful tool for anyone? And how do we make it affordable and accessible to anyone, because it’s not hard to make something, especially now that the tools are so it’s, it’s really easy and possible, if you with a little bit of effort, you can really make anything you want. But to make a product that is going to be robust enough and general enough for a wide variety of people and to make it available off the shelf is a completely different ball of wax, right? And so we we It took us a long time to transition from a little project, a little scrappy project team to a little scrappy startup, we’re still a little scrappy startup. But we definitely you know, we’ve had a pretty slick website that you can go and you can pre order your gloves, they’re still unfortunately pretty expensive, because we’re still right at that edge of being able to manufacture them and making them buy between somewhere between making them by hand and manufacturing them the pieces now we can have manufactured but we still have to do the final assembly.

Rob Head 33:45 Yeah, yeah.

Kelly Snook 33:47 And, and, and really, we’re a hardware and a software company. And so, we we have, we have a hardware product, but we also have a piece of software that works with lots of different hardware. And so we’re trying to you know, we’re really every year we’re getting closer to a proper company with proper marketing and proper, you know, management and and proper, everything proper. But, you know, it has taken us 10 years to get there. So it’s not like a fully mass marketed thing that we can just, like license out to someone or sell. And we’ve never wanted to be the kind of technology company for for many, many years our business structure was as a nonprofit, which is really unusual for a tech company. So we’ve always just had the vision that we want to transform the way music is made rather than make money. So no goal is never been to create this piece of technology, build a company and then sell it, which is what a lot of software and hardware companies do have been we’ve had a completely different mindset from that. We haven’t even wanted to take investment from From typical investment sources, so we’ve always been in this minimum kind of struggle for, for, for funding and just barely making it. But that’s all in order to hold on to, I think the the values that we collectively hold as a as a team. We’re still very small. But I think i think it’s it’s gradually now changing and more people are coming on board. And we’re becoming, we actually had the benefit of being very widely recognized very early on before the technology I didn’t really was ready for that kind of that level of recognition. We had so many people that wanted to buy gloves when Ariana took them on tour, for example.

Rob Head 35:47 Yeah. Tell us about that. What When was that? And how did that happen? How did you end up under the stage at an area on a grand a concert?

Kelly Snook 35:55 Oh, that was in 2014. We were building our first round of gloves that we had sold to a small number of backers that we had found in a in a Kickstarter campaign that we ran. And and so we we were making I was a very small It was like 17 pairs of gloves that we were making. And around the time when we were figuring out how to assemble all those gloves in imagens barn. Ariana came through town and Ariana was a big fan of imagens. And she so Mr. President, I know right? I totally get it now. But she was a really huge fan of imagens and so image and invited Ariana around to the barn, or to house for dinner. Ariana so the club’s Ariana really wanted a pair of gloves. And so since we were in the process of making them we, we decided to make a pair for Ariana. And so she came back round through town around Christmas time that year. And what’s when we were in the barn, really, really working on making them happen. And she came to try them on. And when she tried it on, she decided I really want to take these on tour. But her tour was starting like two weeks later was so crazy. And and so we really had to scramble, first of all to just get the gloves finished, but then also to figure out how to support that. How do we support her taking this experimental technology on this world tour, it was our first tour the honeymoon tour. It was starting in earnest, I think in in February, late February. But the rehearsals started literally two weeks later from when she came to try them on. Right. And so you know, all of us were working other jobs at the time we weren’t none of us is working on me full time. In fact, none of us ever has worked on me mute full time, this company after 10 years where nobody, we’ve never had a full time employee. Wow. And I was the only one really in a position to be able to leave what I was doing and go help get or set up. And we had to we had to come up with all sorts of new technologies very fast. And I worked with my friend Ben Bloomberg at MIT to build a system that would work on the big stage with the gloves, a communication system for the data, and he he was such a rockstar as well and just getting that ready in in a matter of a week he had put together this stage ready data transmission system. He’s now by the way he’s nominated as the producer of Jacob Colliers best record, Grammy, best record Grammy now. He’s just a tech tech genius. And just amazing. You’d

Rob Head 38:56 have to be a tech genius to to be able to contribute anything to Jacob Collier,

Kelly Snook 39:01 right.

I mean, I’ve seen Jacobs looper work without his looper but Ben built a looper and just go live sound. Anyway,

Rob Head 39:12 I just had seen Jacob Collier giving a peek into his studio and his his production process. He’s pretty savvy with Logic Pro you know? Oh, gosh, yeah, no,

Kelly Snook 39:27 I’m Yes. He’s they’re both geniuses. But anyway, Ben is friend of mine from when I was at MIT and at the Media Lab, and so yeah, he helped in that and getting the system ready for Ariana building the rack that we used and you know really making it possible to take these on the road but it was it was touching go you know, every performance I was real nail biter, but but we never had a failure and 85 shows we never had a failure of the technology, which is really remarkable. That is, but it was Yeah. Was that All the knives. Yeah.

Rob Head 40:03 Fantastic. So how does your menu work relate to your professor ship at University of Brighton? Do you? Do you create instruments there? Do you manage? Do you explore there? Do you experiment there? Or is there some? Are they totally separate? How does Yeah,

Kelly Snook 40:25 well, you know, it’s interesting because I, I was on tour with Arianna and and at that tour ended earlier than we thought it might. She just was ready to move on to other other things, I think and and so I was then faced with having left my What are all those stuff I was doing to make money in the UK. And so when I got when the tour was ending, I was I needed to find another job and, and I applied for a couple of academic positions I almost didn’t apply for, for this job at University of Brighton because actually the job that was posted was like a head of Head of School job. And I wasn’t really interested in running a school but right the dean asked me to apply anyway. And then she used that, that application of mine as a way to get me in as an independent adjunct professor, in the UK adjunct professors at different thing, it really meant that I was a full professor, but but part time, so it allowed me and she wanted me to build a fab lab, essentially wanted me to build a digital fabrication lab. Yeah. So that the School of Media could get into. Or at least in my interview, I talked about how that really spawned innovation at the at the Media Lab, and how important it was for people to be able to test their ideas out and build them. And, you know, and this was at a time, this was 2015. So people were really starting to get interested in things like projection mapping, and all these technology, building instruments and new instruments and controllers, and, you know, sensors, and I don’t know, all technology embedded in clothing, and all of these things that the media school media around it to get into. And, and so she hired me to build a lab. But as and as I started getting into that, I started to find a lot of support amongst my colleagues at the university that I wasn’t expecting for the Concordia project. So this, this project that had been brewing in my mind, right, since and it was really during the tour, during during my tour with Ariana, and just before applying for that job at Brighton that I decided, Okay, you know what, I am just going to do this, I’m going to make this the thing, my thing, I’m going to make this an actual project. But I had no idea how to do that, or even how to articulate what it was that I wanted to do. And it was starting to get clear, but I just decided that I was going to put my energies into writing grant proposals to be able to build Concordia, it didn’t even have a name yet, the name Concordia didn’t exist. That was the beginning of me getting serious about trying to figure out how to make Concordia my main thing, but it was still it was low key in my mind until people at the university started really encouraging me to talk about it and do so then I started thinking, Okay, well, I’m gonna build this lab to have a focus on immersive media so that I could use Concordia as a flagship project for, you know, for what is possible there. what’s possible. Yeah. And so that was really, when I started, I got invited to give a talk about Concordia in one place. And once that happened, I started getting every time I would give a talk, other people would invite me to talk about the project. So the project didn’t exist yet. But I started traveling all around the world talking about it. And it was just in speaking about it, that it started to take shape. And, and that, you know, that was the beginning of where I am now, where that’s really my main my main project I do, I’m working on mimio, but mainly for me, is a is a piece of the larger puzzle of immersive, interactive data. sonification essentially, like a gamified way of exploring realities, where you’re immersed in some reality that you want to understand and explain it.

Rob Head 44:25 Yeah, explain data. sonification. Yeah, what what do you mean?

Kelly Snook 44:29 Yeah, so this is I started to get it early on, I got a sense that this was part of what I needed to understand. So that was so when I went to the Media Lab in 2008, was when I really started getting involved with the data sonification community. So if you know what data visualization is, which pretty much everyone know, can can can imagine data, visual charts, because we deal with that all the time. Yeah. And we’ve been doing that for hundreds of years. So really sonification is data visualization, but using sound Instead of visuals, so taking any kind of mathematical or physical, or informational data, and converting it into sound, somehow, the simplest form of this would be, say, taking radio waves, like the rings of Saturn or something and, and converting that down into frequencies that you can hear. That’s the very simplest form of data sonification. But in our day to day lives, for those of us who are hearing and seeing, we, we use, what we see in what we hear together all the time, our brains are wired, to take whatever senses we have, and integrate that all into a model of our reality around us perception

Rob Head 45:43 of reality. Yeah,

Kelly Snook 45:44 yeah. And so but we don’t get to that with scientific data, we just take more and more screens and more and more pages and pages of squiggly lines that you have to flip back and forth to understand or like, or like densely packed visual displays that just are super overwhelming at some point, you can’t take in any more visual data. And I think at that point, we actually have extra channels of perception available to us

Rob Head 46:10 with our more dense then then text, you know, if you think about the spoken voice, yeah, we use that to communicate, but it’s so low density compared to other information that we get from our ears.

Kelly Snook 46:24 Exactly. And our brains are so good at processing that sound. I mean, when you listen to music, there are like five or six different places in the brain that that music gets pumped into, and parallel processing. So you process rhythm in one place of your brain, melody in another place language, and another place harmonics in another place. And the brain just, it farms, it all out processes, all these different things in all different ways. And then connects it into memory and, you know, and other other places to, to give it meaning. And to like, attach it to emotions. And that’s such a complex process, and it happens all day every day with us, and we’re not even recognized realizing it.

Rob Head 47:11 So possibly, the 21st century is all about an audio revolution, whereas the 20th century was all about a visual revolution.

Kelly Snook 47:19 Yeah, maybe me? Yeah. A way like, so. I guess what I’m interested in is making it possible for people to use music. Truly, like, in a truly different way, like more like what it was in the medieval times where music was. instrument instrumental and voice music was the only audible way to mimic the music of the spheres and the music of the human condition, which were two types of music that were in audible.

Rob Head 47:54 And if I recall my music history, they called it, musica universalis. You know, musica Humana. Something like that?

Kelly Snook 48:03 Yes,

Rob Head 48:04 musica instrumentalists or something? Yes. So audible music is is a reflection of the human reality and then the deeper underlying cosmic reality,

Kelly Snook 48:15 the physical world. Yeah. And so that was really it. Music wasn’t entertainment, it wasn’t art. In fact, music was one of the scientists, sciences, it was part of the quadrivium. There was arithmetic,

Rob Head 48:28 Mm hmm.

Kelly Snook 48:31 Astronomy, geometry, okay. And music. And those four things comprise the scientific quadrivium. Those were the tools for our understanding. So let’s see. arithmetic is number. geometry is number in space. Astronomy was number and time. And music is no music is number in time. And astronomy is his number in space and time. And those it was just four different ways of, of understanding number and wants to find things. Yeah, quantifying the world. You

Rob Head 49:05 know, it’s interesting to look at that history of music the world we live in, that you described earlier, where music is commodified as a celebration of of self, essentially order of, you know, a persona. Yes, yes. Yeah. Yeah. You know, I think back to I, you know, I would point to Beethoven as the one that really insisted that it was about his personality. And But before that, you know, certainly, you know, it was a gradual thing that unfolded over centuries, but it’s sort of accepted that in the medieval period, particularly before the Renaissance, yeah, music was didactic, it was there to instruct. Yeah,

Kelly Snook 49:53 yeah. And, and that was the worldview that Kepler had. Yeah. And it actually started shifting right there. But yeah, Beethoven was a couple a couple 100 years after. Yeah. Okay, so the box box music was was also based on the principles that same principles as Kepler’s work. Uh huh. Which people don’t? Really,

Rob Head 50:16 how would you describe that? Yeah. What do you mean when you say that?

Kelly Snook 50:21 I’m just understanding harmonic relationships as an harmonic progression as a mathematical expression as as a, if you look at the mathematics of box work, and the circle of fifths, and a well tempered clavier, and the theory that underlies the work of Bach is the same harmonic theory that Kepler used to discover the way that the planets move

Rob Head 50:58 it as I understand it, that you know, during box time they were really wrestling with getting away from the temperaments that they used at the time that were more closely related to the harmonic series and they were developing temperaments that allowed you to modulite further afield from the original key and so yeah, all of that science was so related to what Bach you know, the reason he will have temper clivia is to prove that you could play in all the keys.

Kelly Snook 51:25 Yeah, exactly.

Rob Head 51:26 Yeah, exactly. Yeah. Hmm. Wonderful. So what are you doing now? Like, what? Where has all of this taken you? And where are you headed? It describe your describe your creative life at the moment, you know, what do you what are you doing? What are you up to?

Kelly Snook 51:42 I’m pandemic eating?

Rob Head 51:43 Yeah. How has that affected your work? Have you been able to find more focus or less focus or how’s that has been treating you?

Kelly Snook 51:55 I have taken a year of rest. You know, I, I’ve taken a sabbatical in a way. And I’ve been reading and studying, you know, I’ve spent a lot of 2020 learning about myself and my brain. Things that I, you know, I was I learning about my neuro divergence. I’ve been learning about racism and systemic racism. I’ve been learning about community building.

Rob Head 52:32 Yeah. Yeah,

Kelly Snook 52:33 in and I’ve been learning I’ve really, I’ve had an opportunity and time to just be in a Wednesday. This is the first time in my adult life that I’ve been in one place for more than three weeks. And I’ve been here now in my studio here for presents February lockdown. And I love hockey. And I’ve just given myself permission to you know, there was a big flurry of activity on Concordia last year, I, I had a sense that if I was going to do what I wanted to do in terms of bringing people together, to, you know, experiment with prototyping, and I was going to need to do it in 2019. I just, I just knew that intent. And instinctively, I don’t know why, but I knew. So I I just quit everything and devoted 2019 to thinking about Concordia, which culminated in three month residency here in Portland with a bunch of people that I invited to think about, to think about the project and experiment and right, so 2019 was a was a really push, push push on Concordia year. And 2020 has been really just a time for reflecting on all of it, and not trying to jump right in and figure out what’s next immediately, just giving myself time to try and digest what I learned from 2019. And from my whole entire life, and also really to look at at society and think about what’s happening in our world right now. And how how will Concordia address these? I mean, really to think at the same level of what started at all, you know, yeah, how could How could I? How can I help to build a world where people can play a musical instrument and understand their oneness? I’ve been thinking about oneness. I’ve been thinking a lot about oneness, and how, you know, the problems in the world right now all essentially stemmed from our failure to recognize our oneness. And since Concordia really is all about allowing people to experience their oneness, oneness with creation and oneness with each other and oneness with themselves and oneness with the divine that’s what Concordia is for. I know that it there’s a role for it to play. It’s still very deeply unfunded. And and also right before the pandemic, I was I was accepted. I was awarded a fellowship in New Zealand to come to New Zealand and build Concordia. They’re beautiful. And then New Zealand shut down, right? And it’s still shut down. So my my visa application is in it’s a three year government impact global impact visa, it’s called. There’s no no direct funding associated with it. But yeah, so I’ve decided I’ve decided that I’m going to wait till I get to New Zealand to take the next formal steps in, in creating Concordia doesn’t mean I’m not thinking about it. But it’s now gone back into more of a background thinking process. I’ve been asked to give a couple of talks about it. So I gave a keynote address a couple weeks ago, at the audio Developers Conference, for example, about Concordia, so I’m still thinking about it. But I’m not I haven’t been pushing on it at all this year, right. And I’ve been doing some music production. I’m working on I work with high artists who set the bar high texts to music. And so that’s just straight up music, music production and composition and arrangement and mixing. So I’ve been doing a little bit of that. But mostly, I’ve been mostly I’ve been resting trying to figure out what it means to prepare for this next phase in our collective developed systems.

Rob Head 56:34 Yeah, it’s,

Kelly Snook 56:36 I think it’s actually going to involve some pretty severe collapses. So I’ve been trying to prepare for that. And really like trance transform into a life where I’m, I’m mainly in one place. I’m so I’m cooking for myself. I’m, I’m, you know, responsible for my own preparation for emergencies. We went through some fires some pretty intense fires that nearly nearly engulfed us, as you’re probably also aware. So there’s been that, you know, 2020 has been a really interesting year. Yeah, stopping. I’ve just really truly been enjoying the stopping and allowing myself to stop a little bit and reflect on so. So in my life, it’s been a year of reflection.

Rob Head 57:27 Well, Kelly, it’s a delight to have you thank you so much for taking time and speaking with us. And I can’t wait to see what happens when you make your way to New Zealand and continue working on your projects. Fantastic. Thank you.

Kelly Snook 57:42 Thank you. My pleasure. Thanks for inviting me. All right.

Damien Burke 58:00 The 52 Sketches podcast is a product of 52 Sketches, makers of earlywords.io. Daily, private, stream-of-consciousness writing to clear mind and unlock your creativity.

Rob Head 58:24 And now the track Patience by our guest, Kelly Snook.