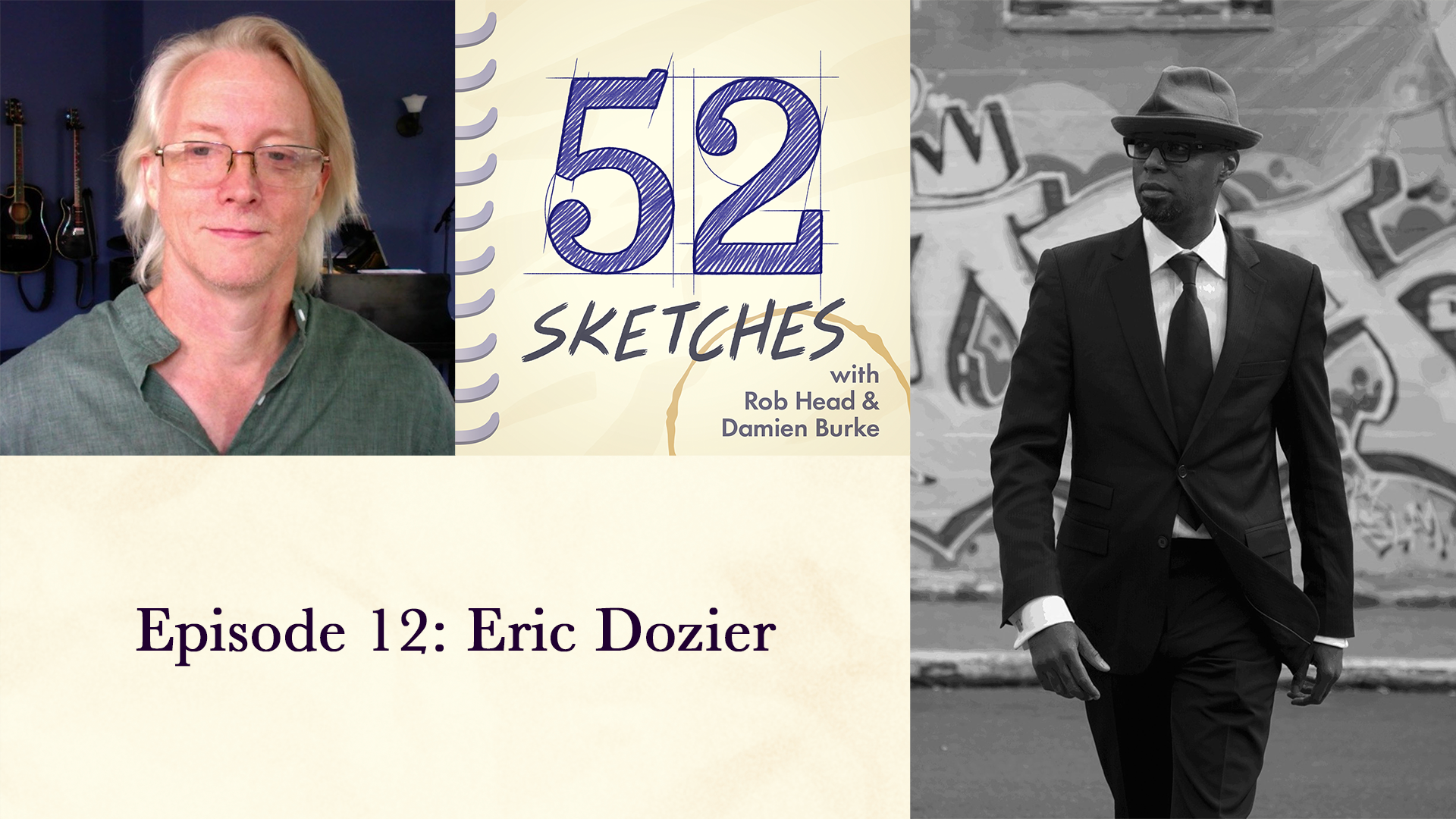

Episode 12: Musician and Activist Eric Dozier

Subscribe: RSS | Apple | Spotify | Google | Sticher | Overcast | iHeart | YouTube

Itinerant blues preacher Eric Dozier discusses growing up surrounded by music in Southeast Tennessee, the value system of Black church music conservatoriums, the universal appeal of Black gospel music, and how he uses music to promote the oneness of humanity.

- Eric Dozier’s website

- Memphis Slim “Broadway Boogie”

- Victor Wooten “Music as a Language”

- United in Praise, formerly the Modern Black Mass Choir

- Louis G. Gregory Bahá’í Institute

- Big Brothers Big Sisters of America

- One Human Family Workshops

- Harlem Gospel Choir

- The Oneness Lab

- Henry Box Brown

- El Sistema

Transcript

Rob Head 0:03 52 Sketches Episode 12, musician and activist Eric Dozier.

Jennifer Head 0:12 Welcome to 52 Sketches, a podcast about creativity and creative practices. Here’s your host, Rob Head.

Rob Head 0:21 Welcome to the 52 Sketches podcast. I’m your host Rob Head. We are here to get to talk about living a creative life, creative practices, habits, strategies for making the world a more wonderful, more beautiful place. Today, we are delighted to be speaking with Eric Dozier, musician, recording artist songwriter, choir director and race unity activist. He describes himself as a cultural activist, anti racism educator and itinerant blues preacher leveraging the power of music to promote healing justice and racial reconciliation. He has served as the musical director for the world famous Harlem gospel choir, the award winning Children’s Theatre Company of New York City, and has been a featured artist at the United Nations. He currently serves as a museum educator for the forthcoming National Museum of African American music in Nashville, Tennessee, and has recently launched the young people’s freedom song initiative, an interactive musical exploration designed to engage young people in revolutionary music making, is a graduate of Duke University and Duke Divinity School and is currently pursuing a doctorate at the University of Tasmania, researching the effects of black gospel music on communities outside of the black church. So welcome Eric Dozier,

Eric Dozier 1:37 hey, hey, hey, How y’all doing?

Rob Head 1:40 It’s been great. It’s great. So good to have you on the on the podcast. So I just want to check in how’s the how’s the pandemic treating you? How’s the family? Everybody?

Eric Dozier 1:51 I love I love it. I love questions like that. How’s the pandemic treating you?

Rob Head 1:57 Yeah, it’s a risky thing. You know, a lot of people and it’s Yeah,

Eric Dozier 2:02 well, we, you know, we, we, you know, we’ve had our share of loss, like most folks, but we’re, you know, we’re making our way through it as a family has to do and it is, I mean, it crazy times, crazy times, but, but, you know, like, I, when I think about all of this, you know, this too shall pass. And it’s, it reminds me of this old spiritual that we used to sing in, at our church, the storm is passing over Hallelu. So, you know, I think, hopefully, we’re coming out on the other end of that. Yeah. You know, I always tell people to just keep singing through it. You know, we’ll make our way.

Rob Head 2:45 Yeah, yeah, we’re describing it as a storm really helps me frame it with a little bit of, maybe there’s a silver lining on those clouds somewhere.

Eric Dozier 2:53 Right. Right.

Rob Head 2:56 So I want to back up to your, to your childhood and your growing up, you mentioned, you know, coming up in the church, and, you know, tell us about where you’re from, and how you how you came up and and, you know, how did you get into a creative life? Did you was that just, you know, part of your existence? Or how did that all happen?

Eric Dozier 3:16 Yeah. So I you know, I grew up in a small rural town in in Tennessee by the name of Bakewell. And yeah, Southeast Tennessee, you know, I’m a country boy, you know, I grew up in the country. And we had, yeah, yeah. So, you know, as far as like, my, my creative life beginning, you know, I can’t really, it’s hard to say when it started because I’d always been surrounded by music. You know, I’ll often say that I was, you know, I took I took my first my first degree from the Conservatorium of black religion and rhythm, which was the mount at Baptist Church. And, and so, you know, my family is really responsible for for my early kind of patchwork music education, which consisted of, you know, playing the piano at at that church from probably five years old until I left Bakewell, but also being able to, you know, come home, and my dad had a, you know, he played all kinds of music. You know, I remember listening to Memphis limb play the piano, and that was kind of my first introduction to wow, you know, what, what in the world is that instrument and then, you know, my parents eventually bought me a little plastic piano and so they would put that Memphis slim record Broadway Boogie on and, and I wish that I would hit it, man, I would just get on that piano. It was like, you know, it was like just hitting the home button and I would be banging on that piano. And then one day, you know, I look out Our window and my dad is coming up the driveway with my grandfather’s truck, and there’s a piano strapped to the back. Right? So I’m looking at this piano, he gets it into the house. And then he sits down and starts playing. That’s the first time I had seen him. I didn’t even know he played the piano, right. And, and so I just watched it used to watch his hands and just do what he did. And, you know, he played blues gospel blues is what he played. And, and that’s kind of how the piano started. And, you know, and then for many years, I just, you know, I directed a choir work with my mom, who was the choir director. And that’s, that’s kind of how I got it. Like, I don’t really have a formal education. Yeah, I mean, you know, but you know, and it’s funny, like when I describe the black church as a Conservatorium, you know, people kind of look at me like that, but I mean, listen, that institution produced Marvin Gaye, Ray, Charles, Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight, Whitney Houston, Cissy Houston, Donny Hathaway, Billy Preston. I mean, you name it, you know, like how many other Conservatorium or conservatories can say that they’ve produced that many genre defining artists, and then on and then and then literally on the only other end of the spectrum, you had people like Paul Robeson, Jesse Norman, Kathleen, battle, sister, Retta, Jones, you know, all these people that were that were also definitive personalities in classical you know, music, you know, they art music, right? fist Jubilee singers. You know, all of the HBCU quartet groups, the Golden Gate quartet, Sam Cooke. I mean, like, come on. And, and so, you know, so, you know, it’s

Rob Head 7:04 a proven, it’s a proven methodology. That’s it. Yeah.

Eric Dozier 7:06 I mean, it really is, and says a lot about a theory of music that really has been able to incorporate different styles and genres. And, and so a lot of my work really spins around, helping people to see that it’s not just kind of a cultural expression of music, but it is a musical methodology. It is it is a particular theory of music that has undergirding values. And, and, you know, and my contention is when we can actually bring these values to bear in multicultural gatherings and situations, that that is the value system that we need to bring the world to a deeper recognition of the oneness of humanity.

Rob Head 7:59 All your all your work sort of makes sense in that context. Yeah.

Eric Dozier 8:02 I mean, you know, you know, there’s a lot of intersectionality that that happens there, you know, and happened from growing up in a place where I was singing, you know, he’s got the whole world in His hands, and I’ve got shoes, you got shoes, all of God’s children got shoes are This little light of mine, you know, I’m gonna let it shine, all these different things, and and it just kind of synthesized into this, you know, beautiful experience. Eric,

Rob Head 8:31 you reminded me of a TED talk? I’m pretty sure it was Victor Wooten. The bass player. Ah,

Eric Dozier 8:37 yeah, yeah. Well,

Rob Head 8:39 just scribing his experience, you know, how he people like, you know, he’s arguably one of the best bass players in the world. Oh, yeah. Definitely. And if people ask him, how did you learn, you know, and, and his description is basically he learned music, like he learned language, it just, he was just immersed in it. And and he described being, I don’t know, two or three years old, and his older siblings are jammin in his house. And he’s, you know, two or three doesn’t know what’s going on, but they’re, like, just stick a bass in his hand, you know, right. And right. And he just from there, just, you know, wasn’t nobody said this is hard. You know, yeah, join, you know,

Eric Dozier 9:20 yeah. And, and nobody said that you have to go through, you know, four to eight years of schooling to know how to do it. Right. Right. Right. Or that you had to look at a piece of paper with little black dots on it. And that’s right. Music, you know, cuz that’s not music. Like that’s a representation of music.

Rob Head 9:39 Right, you know, on style of representation of music.

Eric Dozier 9:42 Exactly. Yeah. Yeah, exactly.

Rob Head 9:44 Yeah. Yeah. Beautiful. So So how did you go from from your small town? From what what I understand from your bio, you went off to Duke University at some point and what did you study there? Did you did you do music or you do other things now?

Eric Dozier 9:59 No, you No, I, when I went to Duke, I went there as a biomedical and electrical engineer, you know, I got accepted into the engineering school there. And which, you know, my high school, you know, I was I was into, like, computer science and and, you know, physics and chemistry and, you know, I was I was I was a nerd, you know,

Rob Head 10:24 yeah, you were in AP APCs.

Eric Dozier 10:29 Like, I took all of the APS and you know, took five years of Latin and all that. And

Rob Head 10:35 I only made it to three man before. Yeah, we ran out of, you know, students

Eric Dozier 10:41 but but you know, it, it helps with the SATs, though, you know, so

Rob Head 10:44 yeah, for sure. And they notice at Duke

Eric Dozier 10:48 Oh, yeah, no, definitely, definitely. And, and so, you know, like, I went there as, as an engineering student, and just, you know, I just kind of felt like, Wow, that’s a lot of time in front of screens and working with numbers, and that I prefer to just do something that was more akin to, you know, community and, and so I switched my, I switched my major to public policy, we’re going to focus on youth race and education. And, you know, and then also took some, some religion and theology classes and African American history classes along the way, and end up, you know, graduating with with that degree, and went on to the Divinity School at Duke and did a master’s in theological studies, which focused on you know, comparative religions, I actually wrote my master’s thesis on the, the rise of Islam in America. And, you know, it was, it was interesting, like writing that as of a high in a Methodist Divinity School, you know, but, you know, I always kept doing my music. So, you know, throughout my time at Duke, I was the, the musical director for the modern Black Mass choir at Duke University. And

Rob Head 12:12 Black Mass choir. Yeah. And, and so, like, Sunday services,

Eric Dozier 12:17 well, now we, you know, we did things all over the city, and, you know, which, which eventually led to us getting a grant from the president of the, the university to go to the Czech Republic, after you know, kind of after everything over there kind of opened up like in the, in the 90s. And, you know, so that was really an experience that really kind of fortified a particular trajectory for me, you know, we were there. And we were doing this song that my great yeah, my great grandmother taught me hold on just a little while longer, everything will be all right. And we were singing that song in a, in a, in a cathedral in Prague. Or it was it Yeah, it was in Prague. And we were singing this song, and it was, you know, all African American choir, college kids. And, and so we sing this song. And it the way the song is really simple song. But it says, hold on just a little while longer, everything will be alright. So we sing this song, this, this lady comes up, Czech, Czech lady comes up, and didn’t speak English, but we had a we had an interpreter there. She takes off her rosary. And she hands it to me. And, and she’s and and you know, before we perform the song, I always talk about how my great grandmother taught it to me. She says, You know, I know, I know, your grandmother. And what she was saying is, you know, I knew I know what your grandmother was singing about. And she gave me this rosary that she had had held for 40 years, you know, you know, from the time that they close the churches until that day, and she said, I know your grandmother. And that’s when I began to really realize that this music that I’d been reared in, you know, really is, is for, you know, as for the world,

Rob Head 14:33 it speaks in a universal way, human condition.

Eric Dozier 14:37 It really does. And, you know, and is and is accessible beyond language. And so that’s, that’s really for me were, you know, really understanding the oneness of humanity was really solidified for me. When when I realized the depth of the communication that was, you know, it wasn’t just the communication between me and that and that and that That, that that older check woman that was there, but it but I facilitated a conversation between my you know my ancestors all the way through to her. And so is it was something that was even beyond what I could have done, you know, I really felt like, you know, and I always tell people, you know, I never say Oh, yeah, I’m from Chattanooga, or I’m from Nashville, you know, so the big cities in Tennessee, I always say in front of a quill, you know, I always introduce them to my family, you know, because my family really put that in me before even having this encounter with this with with this woman who had lived through the the shutting down of the churches and, and, and lived through religious persecution and all these different things, you know?

Rob Head 15:49 Yeah. Yeah, there’s something almost mystical about the power of music from Southeast Tennessee to speak to, you know, a woman in, you know, sort of post, what do they call it? Iron Curtain, you know, post iron?

Eric Dozier 16:06 Rock? Yeah. Right. Right. Yeah. And

Rob Head 16:09 there was there was a, I can only imagine I have been, I have traveled a little bit in Eastern Europe, and just the the collective cultural trauma from that period, is you’re not to mention the all the traumas before it. Right. Right. It is was, you know, palpable, right. Right. And, and I can imagine how electric, you know, black gospel music was in that moment. Yeah.

Eric Dozier 16:38 I mean, they, you know, they, they love that music. But, you know, I think it was, it was so much more than that, I think that they, they just resonated with the story. I mean, because it is a, you know, I liken it to the story of, you know, Moses bringing people into the promised land and liberating them from from captivity in Egypt, I mean, that if there’s any story that is indicative of the, or that, that that could be referred to as the meta narrative of black people in America, it would be go down, Moses, you know, tell them Pharaoh, let my people go. And, and there are so many people that, you know, because we live in a world that is really fraught with oppression and exploitation, and, you know, and, and so many things that there are so many people that resonate with that story. I mean, when you think about even the state of the world, right now, the disparities between the, you know, between the wealthy and the poor, and all of the racism, you know, that, that is manifesting itself globally, you know, as well as locally. I mean, there are so many people that identify with Let my people go, you know, as opposed to, hey, you know, everything is cool, everything is great. Everything is fine. You know, and so, you know, and I think that what black music carries is it just carries this, this particular balance of joy and pain and hope and despair, and, you know, sorrow and jubilation, that it really is more, you know, offers a great descriptor of the human condition, just Yeah,

Rob Head 18:32 yeah. Yeah, fantastic. So, having had this realization and this sort of epiphany that this music can speak universally. Where do you go from there? Like, how did you get from there to I don’t know, the Children’s Theatre in New York City, or what did you do next? Like how did you? Yeah, realization and turn it into some kind of career?

Eric Dozier 18:54 Well, you know, it was it was funny, like I I moved to South Carolina. Okay. For a while after I graduated from you have to finish Duke and went to work at the Lewis Gregory high Institute.

Rob Head 19:14 You’re our second guest. That’s done a stint there. Kevin. Janus was our first podcast guest and he he spent a year there. Yeah. Oh, yeah.

Eric Dozier 19:23 You know, I was I was down there for for quite a bit, helping with some community development type of things. You know, I started working there. And then after I left there, I went to to Columbia, South Carolina. Okay. And I got a job working with the organization, Big Brothers, Big Sisters that you know, I’m sure most most of your audience has heard of them. And, and so my boss comes in one day. And she says, well, Eric, you know, you look really bored at this job. lackey as she as she just asked me, you know, what I, what I what I like to do more with my music and the agency because what one of the issues that that these agencies, you know, like this These matching agencies have a lot of times is when they, you know, everybody wants a younger kid. And the teenagers, you know, if they come into the system too late, you know, they kind of they, you know, they don’t get paired as easily as a younger child would right here. And so she she asked me if I would like to do something with my music. Hmm,

Rob Head 20:39 it’s a sort of in between ages. Yeah,

Eric Dozier 20:41 yeah. Well, it was, you know, these were teenagers, I would say anywhere from, you know, probably 13 to 17 or 18. Like, you know, junior high high school kids. And, you know, after that she and I said, Well, sure. And so, we, we wrote a grant to do this thing called the dream builders club. And we took the older kids and gathered them and helped them write music and put together a musical, that was a that was a composite sketch, creative composite sketch of their lives that was centered around four kids. And so all of their stories were incorporated, and, and made a part of the lives of these four kids that were on this, this journey growing up. And we help them you know, we compose original music, they, they did choreography, they develop the script, and, you know, with the help of, of myself and another colleague who was more theatrical person, a theatre person, and, and then it just kind of started from there. And after that, I partnered with a couple of friends of mine, you know, Carol Williams, and Bill C Davis. At to start one human family music workshops, and, and which is a national chapter, choir chapter organization that uses these forms of African American choral music, to facilitate frank and honest conversations about race in America. And so we started that organization, and it grew and, and, you know, we took a couple of international trips to, you know, to Europe and, and, and then I ended up you know, as, as that organization was evolving, ended up going to New York after meeting Mayor mansoori, who started the Children’s Theatre Company, and this ended up going there to work with them. got an offer to work with the Harlem gospel choir. And, you know, it just kind of, you know, it just kind of blossomed from there from you know, my boss at Big Brothers Big Sisters saying, well, maybe you should try to do something more with your music. And it what it what it did is it actually gave me an incubator, to explore ways to bring my creative side my music, my gifts to bear on racism in America, which eventually grew into kind of a career doing that. Right,

Rob Head 23:31 right. Well,

Eric Dozier 23:33 so you know, what better way strycova Yeah, okay. Some folks have come in. They, they just they just kind of walked into the room Say hi, Worthington. That’s my daughter. And my wife is here. And we you know, they asked me to pop in and do something and we’re at the bar high school that is happening in in with the kids in Nashville, you know, we can’t let go of Nashville. But But would you mind if we shared a little song with you all really quickly.

Rob Head 24:07 That sounds great. Center up that Yeah.

Eric Dozier 24:10 Okay. So, let me see here. Let me turn this. So the This is a song you know, just so that you know, this also kind of ties into you know, what I said earlier about growing up and you know, and Bakewell. You know, one of the first songs that you learned growing up in an African American church is Jesus loves the little children. And so I want to I want to share that with you all, and we’ll see what happens. Okay. You ready Worthington?

Eric Dozier 24:51 Jesus loves the little children All the children of the world Red and yellow, black and white They are precious in his sight Jesus loves the little children of the world

Rob Head 25:37 Yeah. Beautiful.

Eric Dozier 25:40 Yeah, that’s my little girl. My little girl girl Worthington. And she sings quite a bit with me.

Rob Head 25:47 How old is Worthington? She is eight. Oh, beautiful. Yeah, that’s such a great age. It is like, there’s a sense of, like, a maturing mind, you know, while they’re still like, super playful as Right.

Eric Dozier 26:04 Right? I know. Yeah. So we so we go out and, you know, we we ride bikes and play quite a bit. And then I have her, I’ve been doing a lot of consulting work lately, with corporations, companies around diversity, equity and inclusion. And so they so so I always kind of, have her pop in because I integrate music heavily into that work as well. And, and so as a surprise, guest, I always bring her in to help me kind of demonstrate how, you know, really how you imprint these values on children. You know, because she could be listening to any kind of music, but like, I teach her freedom songs, I teach her songs by Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, and all these, you know, all of these artists, these cultural activist and, and, and creative philosophers, and, and that’s how she learns, she learns that, you know, you know, through through that, through that medium, so, and, and, and folks are always surprised, you know, when she, when she comes into the room, and, and she, and she also kind of shares, you know, I give her opportunity to share what those songs mean to her, just to show, you know, you can start to imprint these things on your children early as well, because he, this is the thing, these children that we’re looking at right now, you know, as the song says, red and yellow, black and white, these, these are the children that end up growing up managing these corporations sitting in positions of leadership. And if they haven’t really been engaged in thinking about these particular issues, you know, then when they’re 4550 years old, running this corporation, and you say, Well, hey, you know, our corporation is not diverse enough, we need to do something about, you know, they’re starting from scratch

Rob Head 28:02 that, right, they’re stymied,

Eric Dozier 28:03 they’re like, yeah, so So what so what do you expect? You know, you haven’t, we haven’t had a conversation with our children about this, you know, with our kids, you know, it’s not in the schools, the only place that they can really have it is in the is in the home. And, and then we expect them to be just and we expect them to be equitable, and we expect them to promote diversity when they haven’t had a conversation about it all of their lives. They’re living in segregated communities. And yeah, and have a very segregated cultural experience. So yeah,

Rob Head 28:37 yeah. Eric, I have a couple of things that are on my mind. One is, a couple of weeks ago, in a presentation you gave, you said something that really touched me, which was that the the spirit doesn’t descend? Without song. Yeah. And, you know, I think about that a lot with in my professional life, you know, there’s such a, sort of a dearth of any kind of, like, you know, it’s almost like the humanity is drained out of us that when we walk into the office, you know, and, and it’s painful, right. And so the power of using music as a way to get through some of these ideas that are, it is hard to have an, just a straight up, you know, intellectual mind to mind. You know, you can’t have a change of heart talking to somebody’s mind. Right,

Eric Dozier Right. Right, right. Right. Right.

Rob Head And, you know, so that really touched me. So the other thing is, I want to just tell you, How touching it is to have, you know, an artist who has performed all over the world and been on stage with you know, whoever Nelson Mandela, you know, and and then you know, things for her daughter’s, you know, Sunday school class or whatever. It’s beautiful. It’s beautiful to to see music that’s so integrated into life, instead of being a sort of put into a box or on a pedestal? You know, right. Right.

Eric Dozier 30:05 Yeah. I mean, you know what, man, that’s that, you know, that was a thing. I think, again, I attribute my growing up in Bakewell, and in that incubator man because, you know, my mom always told me, you know, and and, you know, the message that I got from from, from my folks about music is that, you know, son make your music, you know, make sure your music is useful for the community, you know, it wasn’t go out and be a star and make money from doing this. And that, you know, it was always can what can the community do with your music. And, and so much of who I am, you know, you know, we’re taught this kind of rugged individualism in the in the United States, particularly, you know, as if we can actually live isolated from everything else around us. Like, it’s just, I mean, it’s utterly impossible to do that. And so whatever experiences we have, you know, really go to shape who we are and who we who we will become, you know, and I think that the test is to really become aware of how those things shape us, and really take on our own agency in. Okay, so now I know, this is where I came from, and these are the things that have manifested in me thus far. Now, how can I begin to shape those things myself?

Rob Head 31:31 Yeah, yeah. And, Eric, I want to ask you about that, you know, your, your particular background is, is probably unique among the folks that we’ve talked with, on the podcast so far, in the sense that you sort of grew up immersed in your art. And I don’t know that you see it as a separate thing from your daily life, but they do you have, you know, regular practices, daily practices, maybe like, how do you care for yourself, your voice, your, your, your creativity, or the things that you feel like you need to do or have in your life so that you can, you know, have the creative freedom to feel like, Hey, I’m gonna write a new piece, or, you know, I’m gonna Yeah, you know, well, you know, in front of a choir and direct them, you know, like, what do you how do you keep yourself in a place where you feel like, yeah, I can, I can do this.

Eric Dozier 32:22 Yeah, that’s, you know, that, I think that for me that, that, you know, I always kind of, have been hard on myself about not keeping a regular routine. As far as my music is concerned, what I do on a consistent basis is that, you know, I may not rehearse on a consistent basis, but I am performing on a consistent basis. I mean, even since the pandemic, man, I think that I’ve been, I think I’ve performed more this year, you know, through these, you know, through zoom, and these different calls, and, and, you know, in front of so many different people. And so that, that kind of helps me kind of stay current and keeps the the chops up. But, you know, one of the things that I, that I, that I have consistently done is I, you know, I’m constantly observing the world around me, and studying and, and, you know, and, and, and, and trying to keep myself in tune with the spirit of the age. And, you know, that’s through my faith. You know, I’m a, I’ve been a behind for the last quarter of a decade, I mean, quarter of a century, whatever they gave a quarter of a century. And, you know, so that, that I, you know, I engage regularly with the, with the writings and teachings and prayers of the high faith. You know, I’m always reading about current events and, and trying to understand what’s happening in the world. You know, so that my so that my content remains relevant and useful as my mom would always, you know, say, you know, well, you know, what, what uses that music can can we use it? And, you know, and then as far as, like, I guess, developing greater proficiency with my instruments, meaning my voice and my keyboard. You know, if you want to learn to sing, you sing. If you want to learn to play better than you, you, you seek out mentors and other folks. And so I’ve never had really a consistent regimen of like, piano lessons and things like that. But the way I’ve learned to play is that I find artists that I like listening to. And I learned to play their songs. You know, I, you know, I grew up learning how to play the piano listening to Ray Charles, listening to Memphis slim, listening to Nat King Cole and all these all of my piano guys listening to Billy Preston and Donny Hathaway, and training my ear to hear what they were playing and then play it, you know, lick right, you know, and, and I think that that’s, you know, that’s, that also comes from that black church model of really accompaniment and apprenticeship. That’s how you learn it. Like, right, you know, that you learn under the gun. So when you’re sitting at that piano, like literally, if you’re sitting at that piano, at that piano on Sunday morning, and grandma’s comes in? And she says, Well, yeah, hey, you know, baby, I’ve wrote this song on the way to church. You know, I’m just gonna start singing it, I want you to play, you learn how to play in every key. Yep. You know, you learn how to play under pressure, you learn, you know, you, you, you, you kind of just take in this way of playing that is in the moment, and it teaches you immediacy, you know, because the thing is, is that if the spirit is moving in a particular way, you know, as a as an artist that has grown up in, you know, a very spirited black church experience, you learn to move when the Spirit says, move. So it’s anyone who is who is acquainted with those cultural traditions, you know, you you’ll, you’ll know, from that, that I’m not rare like this, you know, I mean, I’ve I’ve taken it and done a particular thing with my understanding of those traditions. But

Rob Head 36:54 that is the tradition that it is.

Eric Dozier 36:56 Yeah. Yeah, it is like that, you know, that’s part of it, this is calling response is improvisation is immediacy and spontaneity. You know, that’s what it is, though. And those are, you know, I refer to those things as cultural values, like, there are cultural values that sit at the base of the of that musical practice, that also will tell you a lot about the people that evolved them. And, and so you know, my practice, man, you know, that, I still carry those things over into my practice. So, if I see and, like now is, what was so great about, you know, gospel and soul and blues is that you can go on YouTube now and see folks that have broken those traditions down. And that can teach you certain things. And so, like, I might find a piano player that I like, and I and I will, you know, I’ll make a playlist of, like, I actually, I literally have a playlist of piano lessons. And so that’s how I get my my mentorship is I find these artists that I like, and I learned how to play these things. And, you know, the other thing about it is that there’s this integration of things that that also takes place, is that you listen to these various artists, and you just learn how to integrate them and evolve your own style. Yeah,

Rob Head 38:19 you know, this is so fascinating to me, because, you know, my, my family comes from the classical, you know, what would be called the classical tradition? You know, the art music from the European tradition, and the methodology could not be more antithetical, right, right, the the way that classical music has calcified, and this is, you know, great schools are getting over this, but, but for the most part, the classical world is one in which you do not even have the right to think about performing until you’re in the top 1%, you know, of all artists, you know, yeah. And so it’s not experiential, it’s not immediate, it’s, it’s okay, right, let’s talk about how you need to study for 10 years before, you know, you’re worthy. Ryan, right. Well, and yeah,

Eric Dozier 39:11 and, you know, you think about that, because, you know, when I when I when I took this you know, this, this started this Ph. D. Program at the University of Tasmania, you know, they gave me this basically, you you got to walk through a particular gate. And that was not even Oh, my that was that gate wasn’t even on my radar, you know, because I didn’t study the old dead white dudes, you know what I’m saying? But this is the thing is that is that when I started to study music, you know, of the people that you know, folks consider to be the greats in the classical realm. You realize that at the beginning, a lot of that music was improvisational.

Rob Head 39:53 Mm hmm. Yeah. You know, Bach, Mozart. Yeah, improvisational.

Eric Dozier 39:59 Yeah. And so and so they would they would probably, you know, be like, why are you trying to freeze me in time like that?

Rob Head 40:08 Yeah, exactly. You know, they totally agree.

Eric Dozier 40:11 Yeah. And and that’s the thing is so so how do we how did we get to the point that we have gotten to even classical music? Right? Where where, you know, your your worth is is really kind of gauged based on whether or not you can replicate what these folks have done.

Rob Head 40:31 Yeah, Eric, you know, I’m gonna I’m gonna dive in here for a second because please do yeah. As I understand it, one of the things that epiphany that I’ve had is that the calcification of the classical tradition has everything to do with the rise of nationalism and racism in the 19th century. So, yeah, yeah, you

Eric Dozier 40:54 know what, let’s, let’s just go on and get it.

Rob Head 40:59 There’s this notion, and Wagner might be the poster child of this, but there’s this notion of the supremacy of German, the German tradition. So Austrian music, right, Mozart, Beethoven, hi. And everybody before and after. And then, and the, you know, even within Europe, there was this notion that German music was superior to French music and English music and Italian, right, like, you know, it was more serious and more moral and more correct and more, right and, and the rise, and you know, and, of course, every nation had their own flavor of why theirs was superior, but the Germans really, really took it to the next level. You know, it really ties into disasters of the early 20th century, you know, all of this philosophic, philosophical idea, that there’s that there’s a racial component to like human greatness really is tied in with this idea that we therefore we need to, you know, lionize a certain period of German music and say, this is this is the pinnacle of music. This is the pinnacle of human achievement, this is the best that can ever be. Right. And and, you know, disaster ensues, you know, right there.

Eric Dozier 42:05 Well, I mean, I think I think that you’re absolutely correct. Now, when you think about what white supremacy is, white supremacy is a philosophy that says that everything that emanates from people who have been racialized as white, you know, because there is no one place that white people come from. Just like there is no one place that black and brown people come from, you know, Europe, Asia, and Africa is that’s one landmass. So if you wanted to, you could walk from the tip of Africa to China, you could get there by foot. And if you want it to swim from Africa to Europe, is 11 miles across the Straits of Gibraltar, right?

Rob Head 42:47 Mm hmm.

Eric Dozier 42:48 So who’s to say, Well, you know, what belongs to who, you know, when we know that the Moors were in Spain for over 700 years. And they were responsible for preserving, you know, the, you know, ancient Greek and Roman text and all these different things when the church when the western church was burning books, and killing people.

Rob Head 43:11 Yep. And because, you know, Spanish music in the, in the classical tradition, Spanish music is sort of shoved aside as, you know, right. Uh, you know, they were obsessed with, like, stringed instruments, and, you know, loot bars and whatever. It’s sort of a side

Eric Dozier 43:26 note. Well, it is and then and then and then when you think about also, you know, if you if you have groups of people that, you know, essentially, you know, came from the western coast of Africa, northwestern coast of Africa, into Europe, and really brought light to the Dark Ages. The Dark Ages. And when you read histories of classical music is as if Islam and Muslim musical traditions had no, you know, had no influence on on this, this art, you know, like, clearly did in

Rob Head 44:08 Spain? Yeah. Right. Like, in Italian, right. Vocal tradition, you know,

Eric Dozier 44:14 yeah. You know, the only way that those things get erased is because we are living in a system that are racist. That erases them just totally erases the contributions and then exhausts them, exalts one subset of the human family over the rest of us. Mm hmm. And that is totally not acceptable. You look across genres, you look at, you know, say black music and black people in country music. You know, like, I mean, the banjo evolved from a West African instrument, right. So, one of the primary staples of country music the banjo is a West African instrument. So how How can you even come to the conclusion that black people had no part in the evolution of that music? When we even know that country music evolved from, you know, a lot of it kind of evolved from these, you know, black string bands that were traveling around the south, all over Texas. As

Rob Head 45:21 recently as right now, you know, this year yeah. Anytime a black artists makes waves in the country, music world, people are freaking out about it. Like it’s

Eric Dozier 45:33 Yeah. I mean, like, like, like, yeah, like, like that, like, that doesn’t belong to us, too. Right. Right.

Rob Head 45:39 Right.

Eric Dozier 45:40 Right. You know, when we when, uh, you know, and that’s the thing is that is that we have to figure out a way to kind of break out of this particular way of racially reasoning about things. Yeah. But also realize that, how do you do that, but still acknowledge the fact that we we still live in a global racial hierarchy? You know, because you can’t you can’t separate that, that way of even historical read of classical music from colonialism and imperialism. Right. You know, it’s, you know, yeah, they’re inextricable, you know, because if if, if a race is superior, then their cultural production is superior. Right, right.

Rob Head 46:26 Yeah. It’s problematic. I don’t know if you’re familiar with like, el sistema in Venezuela, or, which has had incredible Oh, yes.

Eric Dozier 46:33 Oh, yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Rob Head 46:37 Duda mouth, who conducts the Los Angeles Philharmonic is right, you know, probably the most famous conductor in the world. They came out of that system. But it’s interesting, because they’ve created this brilliant, sort of a system of training musicians. Right. But it’s also they’re embracing the the colonialist model, and it’s just, it’s it’s complicated, right? It’s

Eric Dozier 46:58 Yeah,

Rob Head 46:59 yeah. Anyway, yeah. Well, okay, Eric, it’s been such a delight to spend this hour with you. I do want to ask you like, right, uh, you know, what, what is your typical week looks like, you know, what is your what kind of life have you built for yourself? And and what are you working on? What are you trying to get done in the next year to,

Eric Dozier 47:16 man, well, you know, this, man, I, you know, this the whole kind of COVID pandemic thing has, has really, you know, just like everybody else, modified and everybody’s, as kind of had to retool, you know, I’m still involved in writing music. I was been a part of our composer in a musical that was developed by the Children’s Theatre Company around the story of a slave that actually mailed himself to freedom with the help of light minister. His name was Henry box Brown.

Rob Head 47:54 True story.

Eric Dozier 47:55 Yeah, true story. He was a he was he you know, he conspired with a enlisted a white minister to help him mail himself out of slavery to freedom. And, and so we have been working on that. And and now we’re working on you know, it was on tour. One, a, you know, got critical acclaim at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and Oh, nice lrB people are beginning to take notice. And so we’re evolving and moving that project ahead. And, you know, so there are a lot of things that are going on. I’m just right now I’m just trying to figure out how to manage all of this stuff. You know, I actually need a I actually need a new band member you know, that, that that just does that. Yeah, man, a

Rob Head 48:48 personal assistant. Right.

Eric Dozier 48:51 I think it’s time.

Rob Head 48:53 So yeah, yeah. Eric, thank you so much for all the work that you’re doing. And it is the powerful experience of interacting with your your your music, and yeah, yeah, I don’t know. You want to play us out?

Eric Dozier 49:08 Yeah, man. I’ll play you out. So so you know what I will share. Let me share this one a little bit. A little bit of this one here. All right. So this one goes and everybody knows this. So it goes.

This land is your land. This land is my land. From California to the New York island From the redwood forest to the Gulf Stream waters This land was made for you and me

Eric Dozier 49:42 There you go.

Rob Head 50:16 Thank you so much. All right. Well, I hope you have a wonderful week and I hope your work continues to go splendidly.

Eric Dozier 50:24 Thank you, brother. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you and thank you for having me, man. This is a You’re so welcome. Yeah, lovely, lovely, lovely.

Damien Burke 50:45 The 52 Sketches podcast is a product of 52 Sketches, makers of EarlyWords.io, daily private, stream of consciousness writing, to clear your mind and unlock your creativity.